Prairie dog management act repeal proposed

The Agriculture Committee heard testimony March 5 on a bill that would repeal the Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Management Act.

The 2012 act authorizes county boards to adopt and carry out coordinated management programs to control black-tailed prairie dog colonies on property within the county.

The law requires a landowner to manage prairie dog colonies on his or her property to prevent them from expanding to adjacent property if the neighboring landowner objects to the expansion. If a landowner does not provide evidence that a colony is being managed within 60 days of a county board’s notice, the county may enter upon the property to manage the prairie dogs.

A landowner is responsible for any management expenses. Unpaid assessments become a lien on the property and a part of the taxes on the land that bear interest at the same rate as delinquent taxes.

Landowners who do not comply with the law also could be subject to a criminal penalty and be fined up to $1,500. The law allows counties to file suit to collect the debt beyond tax foreclosure proceedings.

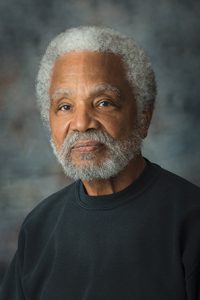

LB45, introduced by Omaha Sen. Ernie Chambers, would repeal the act. He said it deprives property owners of due process by allowing counties to eradicate prairie dogs on a property owner’s land in response to an unverified complaint from a neighboring landowner.

The law requires counties to provide both general and individual notice to landowners who are in violation, Chambers said, but it also states that failure to provide notice does not relieve any person from complying with its requirements.

“This is a bunglesome law which exemplifies government overreach and overkill without any judicial involvement until a spurious criminal charge is filed against [property owners] by the county attorney,” he said.

Chambers said landowners can use non-lethal methods, such as planting hedges and installing artificial raptor perches, to control prairie dogs.

Robert Bernt, a central Nebraska organic farmer, testified in support of the bill. He said an inexpensive raptor perch he built near his fence line keeps prairie dogs on his property from spreading to his neighbor’s.

Bernt said the poison generally used to control prairie dogs is short-lived, allowing the animals to repopulate quickly, and it kills birds and other wildlife. Most importantly, he said, if the county were to spread poison on his land based on a neighbor’s complaint about unmanaged prairie dogs, he would lose his organic certification.

“This is an intrusion on personal property rights,” Bernt said. “That’s all there is to it.”

Jocelyn Nickerson, Nebraska state director for the Humane Society of the United States, also testified in support. She said prairie dog colonies provide food and shelter for burrowing owls, foxes, eagles, badgers and the endangered black-footed ferret. Prairie dogs used to number in the hundreds of millions, she said, but their populations have decreased more than 95 percent due to eradication and human-animal conflicts.

“Moving forward together with common sense solutions for wildlife will keep Nebraska’s prairie dogs and our landowners out of dramatic, dangerous and costly conflicts that are detrimental to our local ecosystem,” Nickerson said.

Matt Gregory testified in support of LB45 on behalf of the Nebraska Farmers Union. He said the act is “unnecessarily heavy-handed” and strains relationships between neighbors. Landowners should be able to decide what to keep on their land, Gregory said, whether that’s prairie dogs or wind turbines.

“We don’t like the idea of a landowner encroaching upon a neighbor who wants to keep prairie dogs, just as we don’t like a landowner encroaching upon a neighbor who wants to manage them,” he said.

Michael O’Hara testified in support of the bill on behalf of the Nebraska chapter of the Sierra Club. He said the act is “an egregious use of the state’s eminent domain power” and that due process is central to the protection of all rights, especially property rights.

“The existing statute has the most minimal due process that is constitutionally feasible in any context,” O’Hara said.

No one testified in opposition to the bill and the committee took no immediate action on it.