Process proposed to assist in death for terminally ill

Members of the Judiciary Committee heard testimony March 15 on a bill that would provide terminally ill patients access to aid-in-dying medication.

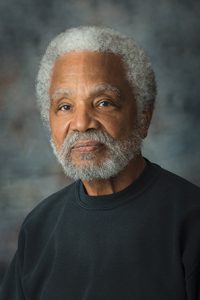

Under LB450, introduced by Omaha Sen. Ernie Chambers, an adult diagnosed with a terminal illness — with less than six months to live — and capable of making his or her own medical decisions, could request a prescription for aid-in-dying medication.

A person would not be eligible for medication based solely on age or disability and the medication would have to be self-administered by the patient.

Chambers said denying a dying person the right to end his or her life in a humane, dignified manner is insensitive and wantonly cruel. Someone who finds the bill’s provisions abhorrent is free to personally reject the choice, he said, but should not be able to prevent others from doing so.

“When it comes to the most significant and portentous decision in a dying person’s life, no third party — including the government — has the right to interfere with, impede or countermand the wishes of the person,” he said. “For the government to withhold from such a person the right and means to carry out his or her final decision is totally unjustified, inexcusable and unacceptable.”

To receive a prescription under LB450, a qualifying patient would:

• have a diagnosis of terminal illness from an attending physician;

• express a wish to receive the prescription voluntarily and without coercion; and

• demonstrate the physical and mental ability to self-administer the medication.

A request for aid-in-dying medication would be made orally and in writing to an attending physician. The written request must be signed and dated by the patient in the presence of two witnesses who can attest to his or her capacity to make medical decisions and that the decision was made voluntarily and without coercion.

The bill requires that one of the witnesses not be related to the patient by blood, marriage or adoption, entitled to any portion of the patient’s estate upon death, or the owner or employee of a health care facility where the patient is receiving medical treatment.

An attending physician would determine whether the patient requesting aid-in-dying medication has a terminal illness, has made the request voluntarily and is qualified to receive the medication. Upon reaching a qualifying determination, the attending physician would refer the patient to both a consulting physician for confirmation of diagnosis and a mental health professional for confirmation of mental capacity to make medical decisions.

Jenna Hyde, representing the National Association of Social Workers, testified in support of the bill. She said a core value of social workers is respecting the dignity of each person and patients’ rights to make decisions about their own care.

“If a patient has the desire, the patient should be allowed to end their suffering on their own terms so that they can experience the dignified death they deserve,” she said.

Opposing the measure was Michael Chittenden, executive director of the Arc of Nebraska. He said there is a common misperception that individuals with developmental disabilities experience a poor quality of life. Families, friends and health care workers could unduly influence these individuals to end their lives if LB450 were to be enacted, Chittenden said.

“There is a long and documented history of our constituents being unduly influenced by health care workers, doctors, social workers, family and friends,” he said. “A guardian, family member or friend could collude to assist someone in taking a pill that they really don’t want to take.”

Nate Grasz, representing the Nebraska Family Alliance, also opposed the bill. He said taxpayers who morally oppose suicide would be forced under the bill to fund a person’s suicide if the terminally ill patient is on Medicare or Medicaid. Lawmakers should focus on providing quality palliative care for those at the end of their lives, Grasz said.

“We can all agree that end-of-life decisions are incredibly difficult but this bill compromises the doctor-patient relationship and creates more problems than solutions,” he said. “We should respond with true compassion and care, not a prescription for death.”

Health care providers may choose whether to provide aid-in-dying medication and would not be held criminally or civilly liable for practicing in good faith under the bill. However, any person who knowingly forges, alters or intentionally destroys a written request for medication would be guilty of a Class III felony.

Similarly, any person who coerces or exerts undue influence on a person to request medication also would be guilty of a Class III felony. A Class III felony could result in one to 20 years’ imprisonment, a $25,000 fine or both.

The certificate of death would report the terminal illness as the cause of death, not suicide, for any patient who dies as a result of aid-in-dying medication.

The committee took no immediate action on the bill.